A historical perspective on football from writer Stewart Pringle

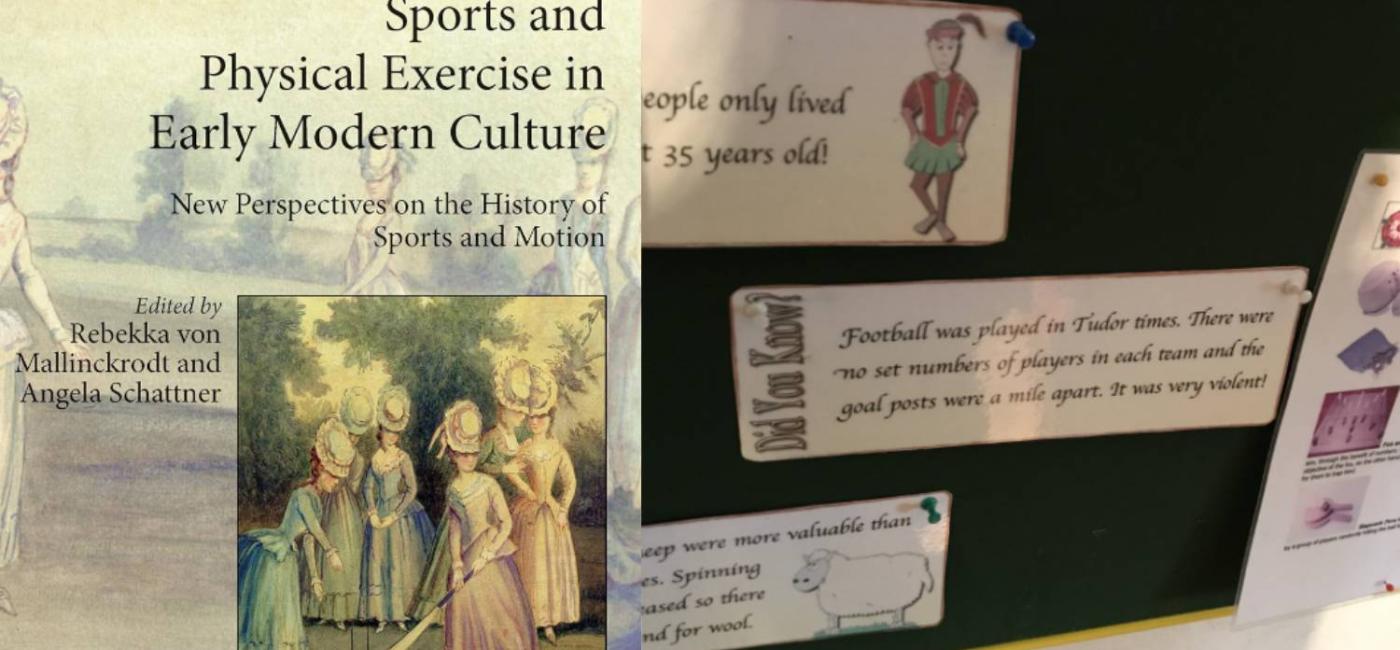

The Bounds owes its beginning to two sources of historical information. One was an essay in a weighty academic textbook titled Sports and Physical Exercise in Early Modern Culture: New Perspectives on the History of Sports and Motion, and the other was a small laminated piece of card in the Tudor House, Margate. The former is a superb and wide-ranging article by Professor Stephen Gunn of Merton College, Oxford and Dr Tomasz Gromelski of Wolfson College, Oxford. The second is, I suspect, intended for children. I came across it on a day out with my wife in 2018, and actually took a photograph of it at the time.

'Football was played in Tudor times. There were no set numbers of players in each team and then goal posts were a mile apart. It was very violent!' But it was enough to set the idea in motion. Of two players, on a vast field, neglected by the rest of their team, playing a primitive ball-game in the mud and the chaos of Tudor England.

Obviously the next step was to acquire a reputable history book and begin to polish up that very dusty Year 6 Tudor knowledge, so naturally I did what any self-respecting researcher would do and turned to 'Terry Deary's Horrible Histories: The Terrible Tudors'. Loads of great stuff in there, and a sentence or two about football - probably the same sentence which had inspired the laminated card in the Tudor House. So I had to go a bit deeper.

That's where Gunn and Gromelski came in. Their article 'Sport and Recreation in Sixteenth Century England: The Evidence of Accidental Deaths' blew the play wide open. Their thesis is that there are precious few ways to ascertain evidence about Tudor football, or any sport played so long ago, in such an unrecorded and organic manner. There were no sports papers, or reporters. There were no printed league tables or championships. So to uncover evidence about the games, you rely on those things which are deemed important enough to record - legislations and deaths.

Deaths, and terrible injuries more generally, allow us to make rough guesses as to the location and dating of these most violent football games. Sudden spikes in the death-rates among the youth of a small village over a feast-day weekend, particularly when coupled with reports from coroners and the assizes can point to the presence of the kind of bloody, murderous game that Percy and Rowan find themselves on the fringes of in The Bounds.

Legislations, on the other hand, which in this context usually means prohibitions, allow us to track the details of these games through the statutes and disputations, parliamentary and ecclesiastical, which sought to limit their spread and influence. What became clear through Gunn and Gromelski, and through the wider range of articles Professor Gunn recommended to me, was that even activities as apparently innocent and celebratory as public sporting events constantly fell victim to changes in governance and orthodoxy in the turbulent 16th century. Games were railed against, and banned, whether as part of a larger crackdown on activities on feast days such as Whitsun and Rogation, or for their specific deleterious impact on the population.

Without giving too much away about the directions this long strange game takes for Percy and Rowan, the experience of researching and writing the play was one of a constant widening and (I hope) deepening of its concerns and themes. Mirroring what happens to poor Rowan and Percy, the ball game becomes a much larger struggle, the violence more widespread and terrible, and the weft of local rivalry becomes woven into a vastly more universal picture of violence and oppression.

Any writing process, for me anyway, begins with a simple anxiety 'is there a story there?' or maybe 'is there ENOUGH of a story there?'. That first morning in Margate, with two players on a muddy pitch, I doubted that there was, but the more I tugged on the threads, and the more I learned about the period and the real impact of the Reformation on the lives of those most distant from its causes, the wider the pitch became, and the deeper and more promising the earth beneath its surface.